Fire protection piping systems in high-rise buildings are often designed under intense time pressure. Pipe sizes are calculated, valves are specified, layouts are coordinated, and drawings move quickly toward approval. On paper, everything looks controlled. Yet many systems that pass inspection without issue begin to behave unpredictably only after they are placed into service.

The difference is rarely a single mistake. More often, it comes from early assumptions that felt reasonable at the time. Assumptions about how water will move, how pressure will dissipate, or how components will respond once the building is occupied. In tall buildings, those assumptions tend to matter more than anyone expects.

Pressure surge and water hammer risks in high-rise fire piping systems do not usually announce themselves during design reviews. They show up later, when the system stops being theoretical and starts behaving like a real, dynamic network.

What Fire Protection Piping Systems Face in Real Operation

At their core, fire protection piping systems are expected to deliver water to sprinklers or suppression devices the moment they are needed. That expectation is straightforward. What complicates matters is everything that happens before and after that moment.

In a high-rise, piping remains pressurized for years without meaningful flow. Daily temperature changes introduce small expansion and contraction cycles. Pumps vibrate, even when idle. Water quality shifts as municipal supplies change or internal storage ages. None of this is dramatic on its own, but together it shapes how the system ages.

When a system activates, conditions change instantly. Flow accelerates, pressure redistributes, and components that were static for long periods suddenly have to react. Connections that seemed rigid now experience movement. Valves that rarely operate are forced to close or open under load. In tall risers, the energy involved is not trivial.

A system can meet every code requirement and still feel unstable in practice. That lesson usually arrives later than anyone would like.

Why High-Rise Buildings Amplify Pressure Events

Vertical height changes the rules

Height is not just a geometric challenge. It fundamentally alters hydraulic behavior. In tall fire risers, static pressure at lower levels can be significant, while upper sections remain more sensitive to transient changes. This imbalance creates conditions where pressure disturbances travel faster and dissipate more slowly.

The taller the riser, the less forgiving the system becomes. Small disturbances that would be absorbed in low-rise installations can propagate through dozens of floors.

Stored energy in long risers

A long column of water behaves like a spring. When flow changes abruptly, the energy stored in that column must go somewhere. If the system lacks adequate damping, that energy concentrates at specific points. Valves, fittings, and supports are usually the first to feel it.

This is why pressure-related issues often appear near pumps, zone boundaries, or isolation points rather than along straight pipe runs.

Noise is often the first sign. Not failure. Just sound. Systems that “bark” or thump during testing are telling a story long before anything breaks.

Pressure Surge and Water Hammer: Where Confusion Starts

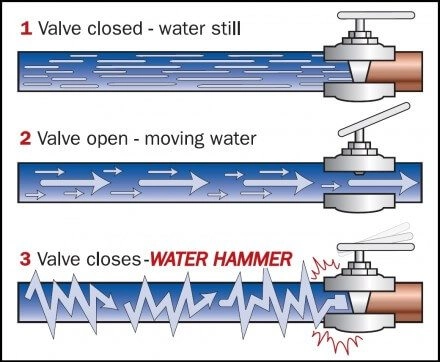

These terms are often used interchangeably, but treating them as the same problem leads to incomplete decisions.

Pressure surges describe transient changes in system pressure caused by rapid flow variation. Water hammer is one form of surge, typically associated with sudden valve closure or flow reversal. In practice, high-rise fire systems experience a range of transient behaviors, not all of which fit neatly into textbook definitions.

What matters more than labels is frequency and repetition. One pressure event rarely causes damage. Repeated events, even modest ones, slowly introduce fatigue. Over time, joints loosen, seals wear, and supports begin to shift.

Most long-term issues are not caused by a single dramatic incident. They are the result of many small ones that were never fully acknowledged.

Common Triggers in Tall Fire Protection Systems

Pump start and stop behavior

Fire pumps introduce dynamic forces that are often underestimated. During testing or routine cycling, rapid acceleration and deceleration of flow can generate pressure waves that travel through the system. In tall buildings, those waves reflect and interact in complex ways.

Systems that appear stable during static tests may behave very differently when pumps engage under real conditions.

Valve closure and flow reversal

Check valves and control valves play a critical role in managing flow direction and isolation. Their behavior during closure matters as much as their pressure rating. In tall risers, fast closure can introduce sharp transients that stress downstream components.

Placement also matters. A valve installed without considering its relationship to pumps or zone boundaries may unintentionally amplify pressure changes.

Zoning and floor isolation

Fire systems in high-rise buildings are typically divided into zones. Each boundary represents a transition point where pressure behavior changes. Poorly coordinated zoning can create localized areas where pressure events concentrate rather than dissipate.

These effects are rarely obvious on drawings. They emerge once the system is operating as a whole.

Where Damage Actually Accumulates Over Time

Contrary to expectation, failures seldom occur in straight pipe sections. They tend to appear at interfaces. Joints, valve connections, branch takeoffs, and support points carry the cumulative effects of transient loading.

Fatigue, not overload, is the usual culprit. Materials and components may be fully capable of handling peak pressures, yet repeated stress cycles gradually weaken them. Over years, what started as acceptable movement becomes noticeable wear.

This is why pressure-related risks should be viewed as aging mechanisms rather than immediate threats.

Why Code Compliance Alone Is Not Enough

Fire protection codes establish minimum requirements for safety and functionality. They are essential. They are also not designed to predict how a system will age under specific building conditions.

Codes confirm that a system can perform its intended function. They do not guarantee quiet operation, low maintenance burden, or long-term stability. Those outcomes depend on design judgment and component behavior beyond compliance checklists.

Passing inspection is not the same as staying predictable for decades.

Risk Awareness Before Jumping to Solutions

Many discussions about water hammer focus immediately on mitigation devices or layout changes. Those solutions matter, but only when the underlying behavior is understood.

Without recognizing how height, stored energy, valve behavior, and zoning interact, mitigation efforts often miss their target. Effective management starts with acknowledging where risk originates and how it propagates through the system.

This awareness is what separates systems that remain uneventful from those that require ongoing attention.

Component Behavior and System Integration

Fire protection systems behave as integrated networks. Pipes, fittings, valves, and supports do not act independently once the system is pressurized.

Fluid Tech Piping Systems (Tianjin) Co., Ltd. supplies piping components used in fire protection applications, including grooved fittings, valves, and related accessories. In practice, the emphasis in many projects is not on individual product features, but on how consistently components perform together under changing conditions.

When components are selected with system behavior in mind, pressure events become more manageable. Installation is smoother, and long-term service tends to be more predictable.

About Fluid Tech Piping Systems (Tianjin) Co., Ltd.

유체 기술 파이핑 시스템 (천진) Co., Ltd. focuses on piping systems and components for fire protection and fluid conveyance. The product range includes pipes, fittings, valves, and system accessories designed to support reliable installation and operation across different building types.

With experience in varied operating environments, the engineering team works with customers to align component selection with system intent, installation realities, and long-term maintenance expectations. These factors often determine whether a fire protection system remains stable long after handover.

결론

Pressure surge and water hammer risks in high-rise fire piping systems are rarely the result of one poor choice. They develop when early assumptions go unchallenged and small behaviors are overlooked. Height amplifies energy, repetition introduces fatigue, and systems age whether designers plan for it or not.

When design decisions reflect real operating behavior rather than ideal conditions, fire protection systems become quieter, more predictable, and easier to maintain. That reliability is rarely accidental.

FAQs

Why are pressure surge issues more common in high-rise fire systems?

Tall risers store more energy, and pressure changes travel farther, making transient effects harder to absorb.

Is water hammer always a sign of bad design?

Not always, but it often indicates that system behavior under dynamic conditions was underestimated.

Can pressure surge risks be eliminated completely?

Complete elimination is unrealistic. The practical goal is managing and reducing their impact over time.

Which components are most affected by repeated pressure events?

Valves, joints, fittings, and support points tend to accumulate fatigue first.

When should designers consider surge behavior in a project?

As early as possible, before layout, zoning, and component placement become fixed.