Water hammer is one of those problems that rarely announces itself during design reviews. On drawings, tall fire risers look orderly and predictable—vertical pipe runs, zone valves at clean intervals, pumps sized with comfortable margins. Everything appears controlled.

Then the system is tested.

Or worse, activated unexpectedly.

Sudden noise. Pressure spikes. Valves that “feel” too aggressive. Pipe movement where no one expected movement at all. In high-rise fire protection systems, water hammer doesn’t usually come from a single mistake. It comes from how multiple reasonable decisions interact once gravity, height, and flow velocity enter the equation.

Managing water hammer in tall fire risers is less about eliminating it entirely and more about understanding where energy accumulates, how it releases, and which design choices quietly amplify or soften that release.

Why Tall Fire Risers Are Especially Vulnerable

In low-rise buildings, pressure changes dissipate quickly. Pipe lengths are short. Elevation differences are modest. A fast-closing valve might cause a momentary disturbance, but the system absorbs it.

High-rise risers behave differently.

Vertical distance creates stored energy. Static pressure at the base of a tall riser can be substantial even before pumps engage. When flow conditions change abruptly—pump start, valve closure, zone isolation—that energy has to go somewhere. The taller the column, the less forgiving the system becomes.

What makes this worse is predictability. Designers often assume fire systems are “normally static,” activated only during emergencies or testing. In reality, tall buildings experience frequent partial flow changes: jockey pumps cycling, sectional testing, maintenance isolation, tenant modifications. Each event introduces a pressure transient.

Most water hammer incidents in high-rise fire systems don’t happen during fires. They happen during routine operations.

How Water Hammer Actually Forms in Fire Risers

Water hammer is often described as a shock wave. That’s accurate, but incomplete.

In tall fire risers, hammer effects usually develop from velocity change, not just sudden stoppage. When flow accelerates or decelerates faster than the system can absorb, pressure waves reflect along the riser. These reflections interact with valves, fittings, and changes in direction.

Some closures are obvious. Others aren’t.

A check valve snapping shut after reverse flow.

A zone control valve closing faster than expected.

A pump transitioning from idle to full load more abruptly than calculations assumed.

Individually, these actions may seem harmless. Combined with height and stored pressure, they create a system that reacts sharply.

The problem is rarely one component. It’s timing.

The Role of Check Valves in Tall Risers

Check valves deserve special attention in high-rise systems, not because they are flawed, but because their behavior is often underestimated.

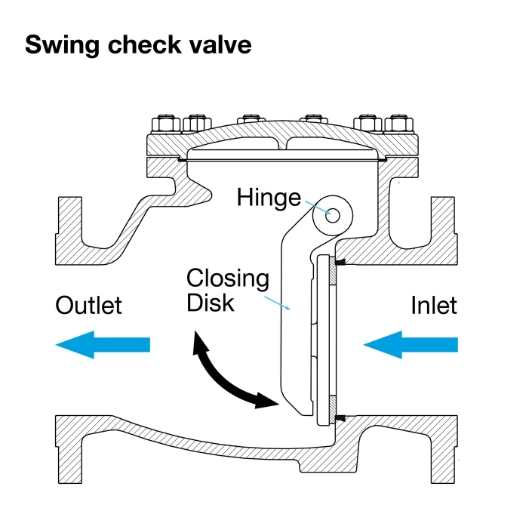

A check valve’s job is simple: prevent reverse flow. The way it accomplishes that task matters far more in tall risers than in horizontal runs.

Traditional swing check valves rely on gravity and flow reversal. In tall vertical risers, reverse flow can build significant velocity before the disc closes. When it finally seats, the impact can be abrupt. That closure sends a pressure wave downward, often toward the pump discharge.

Spring-assisted or dual-plate designs change that dynamic. They respond earlier, closing before reverse velocity becomes significant. The difference may not show up in steady-state calculations, but it becomes obvious during transient events.

This isn’t about “better” valves. It’s about matching closure behavior to system height and operating reality.

Pump Behavior: The Starting Point of Many Surges

Fire pumps are powerful by design. In tall buildings, they must overcome elevation head quickly and reliably. That requirement introduces risk.

Hard starts generate rapid acceleration. If the downstream system cannot absorb that acceleration smoothly, pressure surges follow. Variable frequency drives help, but they are not a cure-all. Their effectiveness depends on programming, response time, and coordination with system valves.

Another overlooked factor is pump testing. Weekly or monthly tests often involve rapid changes in flow, especially when valves are opened or closed manually. These routine actions can stress the system far more often than emergency activation ever will.

If a system experiences water hammer during testing, it will experience it during emergencies too.

Pipe Layout and Geometry: Where Energy Collects

Vertical systems magnify small layout decisions.

Long uninterrupted riser runs allow pressure waves to travel farther before dissipating. Sudden changes in direction—offsets, horizontal branches, tight elbows—become reflection points. Each reflection alters wave timing and intensity.

Designers often focus on minimizing friction loss, which is reasonable. But layouts optimized purely for friction can inadvertently create conditions where transients travel with little resistance.

Sometimes, a slightly less “efficient” path produces a more stable system.

Supports matter as well. Rigid anchoring at the wrong locations can concentrate stress during pressure events. Conversely, allowing controlled movement at predictable points helps the system absorb energy instead of fighting it.

Why Codes Rarely Save You from Water Hammer

Fire protection codes focus on performance during fire events. They address coverage, discharge density, and system reliability under emergency conditions. Transient behavior during normal operation receives far less attention.

This creates a false sense of security. A system can be fully compliant and still experience damaging pressure surges. Inspections don’t usually capture transient behavior unless it is extreme.

As a result, water hammer often becomes a “maintenance issue” rather than a design discussion. By then, options are limited.

Practical Design Choices That Reduce Risk

Managing water hammer does not require exotic solutions. It requires disciplined decisions.

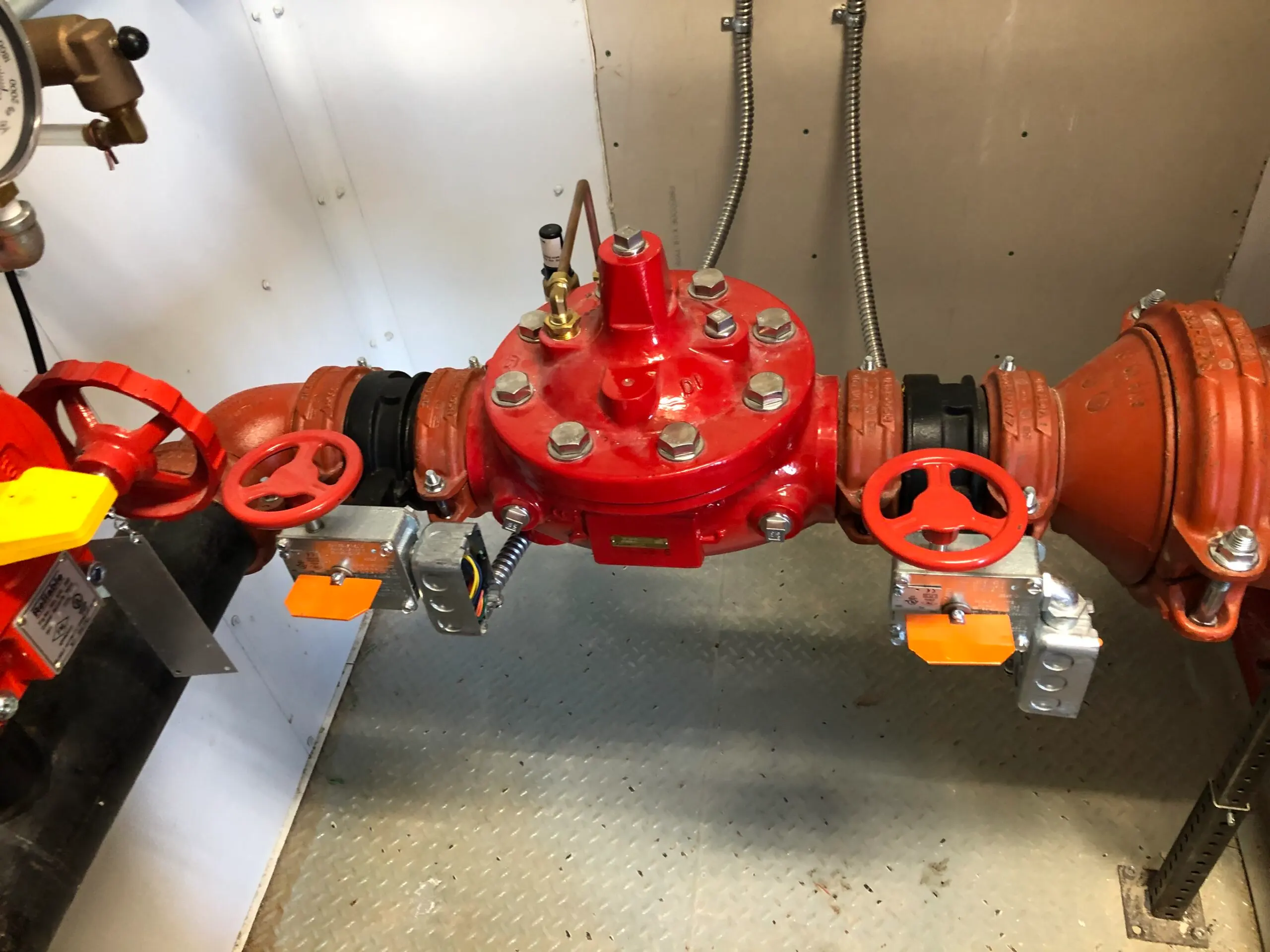

Valve selection should consider closure speed, not just size and rating. In tall risers, slower or assisted closure often outweighs marginal cost differences.

Pump control strategies should be reviewed alongside system layout. A pump that ramps smoothly into a poorly configured riser still creates problems.

Riser segmentation matters. Breaking tall columns into zones with properly located control points reduces the amount of stored energy released during any single event.

Access matters too. Valves that cannot be exercised regularly become unpredictable. Predictability is the enemy of water hammer.

Installation Reality Cannot Be Ignored

Even the best design is filtered through installation conditions.

Alignment tolerances, field modifications, and schedule pressure all affect how a system behaves. Grooved mechanical connections are widely used because they accommodate minor misalignment and reduce installation time. They also introduce a degree of flexibility that helps dissipate transient energy.

This flexibility is not sloppiness. It is controlled compliance.

Systems built with no tolerance for movement tend to express that rigidity during pressure events.

Learning from Systems That Behave Well

Well-performing high-rise fire systems share patterns.

They are not over-constrained.

Their valves are accessible and regularly operated.

Their pump behavior is understood, not assumed.

Their designers accepted that transients are part of reality, not anomalies.

These systems don’t eliminate water hammer. They manage it.

Engineering Perspective from Fluid Tech Piping Systems (Tianjin) Co., Ltd.

유체 기술 파이핑 시스템 (천진) Co., Ltd. works with fire protection projects where tall risers, high static pressures, and demanding site conditions are common. The focus is rarely on individual products alone. It is on how fittings, valves, and connections behave together once the system is pressurized and operational.

Experience across high-rise installations shows that reducing installation friction, improving consistency, and allowing controlled movement often contribute more to long-term stability than theoretical efficiency gains.

When component behavior is considered as part of a system response—not isolated specifications—pressure-related issues become easier to predict and manage.

결론

Water hammer in tall fire risers is not a mystery, and it is not a failure of compliance. It is a consequence of energy moving through vertical systems faster than designers expect.

Managing it starts early. With valve behavior. With pump control assumptions. With layout decisions that acknowledge gravity and height. Systems that account for these realities tend to stay quiet—not just during inspections, but over decades of operation.

Predictability, not perfection, is the real goal.

FAQs

Why does water hammer appear more often in tall fire risers?

Because height increases stored energy and amplifies the effect of rapid flow changes.

Are check valves a common cause of pressure surges?

They can be, especially if closure behavior allows reverse flow to build before seating.

Do variable speed pumps eliminate water hammer?

They reduce risk, but system layout and valve behavior still matter.

Can water hammer occur during routine testing?

Yes. In many buildings, testing events create more transients than actual emergencies.

When should water hammer be addressed in design?

Before layout and component decisions are finalized, not after installation.